A New Generation of Android Click-fraud Apps is Causing Concern

- Android adware apps became smarter and more versatile than ever

- Scammers look to maximize their ad revenues through new techniques

- 22 apps removed from Google Play Store, but this may get a lot harder in the near future

As revealed by Sophos Labs recently, there’s a new set of Android click-fraud apps that features a new level of sophistication in their operation, maximizing their ad revenues while in the same time keeping their activity more intricately hidden.

More specifically, Sophos Labs found 22 adware applications that were downloaded more than 2 million times in total, and while they became originally available up to three years back, they have turned rogue last summer. After their reporting to Google’s Play Store, they have now been removed, but the sophisticated functionality that takes place literally under their hood shows an alarming new generation of adware that will be harder to identify for users and ad serving platforms alike.

Starting with the users, these apps offered the promised functionality, and in some cases, they came with notably modern and user-friendly interfaces, indicative of a high-quality piece of software that users can trust easier. Whilst the user operated the fraudulent application; the latter functioned in the background by communicating with a command-and-control server (C2) that in turn directed the malware to send ad requests to ad serving agencies. Even if the user closed the app, the ad-serving activity was still active in the background, communicating with the C2 server every 80 seconds. Without the user being actually served with the ad in their device, suspecting this background activity was quite tricky. Even if the user reboots the device, the malware would re-activate itself automatically.

The above completes the methodology by which these apps kept their activity hidden from the users, and the only thing that could unveil their operation would be the seemingly inexplicably high battery and internet data usage that would point to them. What about outsmarting the ad networks’ fraudulent detection algorithms though? According to Sophos, this is another part of the sophistication of these new-gen adware apps.

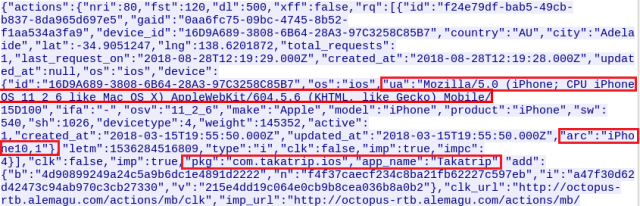

The server would instruct the malware to send ad requests that seemingly originate from a variety of applications and not just the one that orchestrates the whole process. In addition to this, the server used a wide range of device identification signatures, ranging to 249 models from 33 brands. The context of realism was complemented by Android OS version differentiation, starting from 4.4.2 and going up to 7.x. This made it harder for the ad serving networks to detect that something is wrong, as variety in the requests created a false-realism figure. What is even more interesting is that the adware sent quite a few requests from what seemed to be iPhone devices as well, as the ad compensation for iOS devices is significantly higher.

The new generation of Android app malware is more persistent and versatile than ever, and the techniques that need to be applied in order to pinpoint these adware apps among the millions that are out there need to develop as well. Users can protect themselves by regularly checking the battery drain and data usage of their apps, as even apps that were clean previously may turn to adware at any time.

Have you had an Android malware experience? Let us know in the comments below, and also don’t forget to visit our socials on Facebook and Twitter to join the discussions of our community.