Fitness Tracking Platform Exposed 61 Million User Records

- A platform that was aggregating data from various fitness tracking apps and devices exposed everything via an unprotected database.

- The details that were left accessible online include full names, location, and sensitive health data measurements.

- In total, 61 million records were exposed, but the owner of the database has secured now.

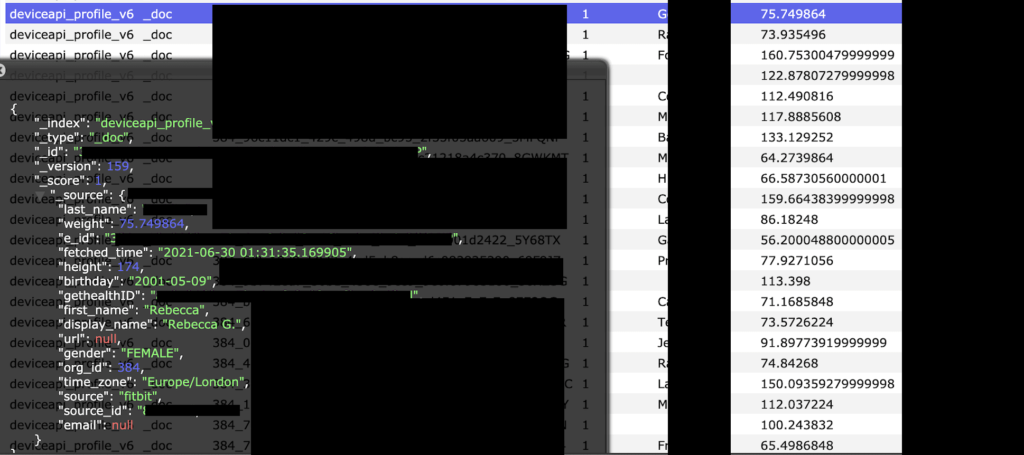

Yet another unprotected database has been left online for anyone with a valid URL and a web browser to access it. This one contained over 61 million records belonging to fitness tracking apps and wearable devices users. The database owner is a New York-based company named ‘GetHealth,’ which offers a platform for users to import their fitness data from various apps through syncing and essentially unify everything under a single entity. As such, the exposure is far-reaching and widespread, but none of the source apps are responsible for this.

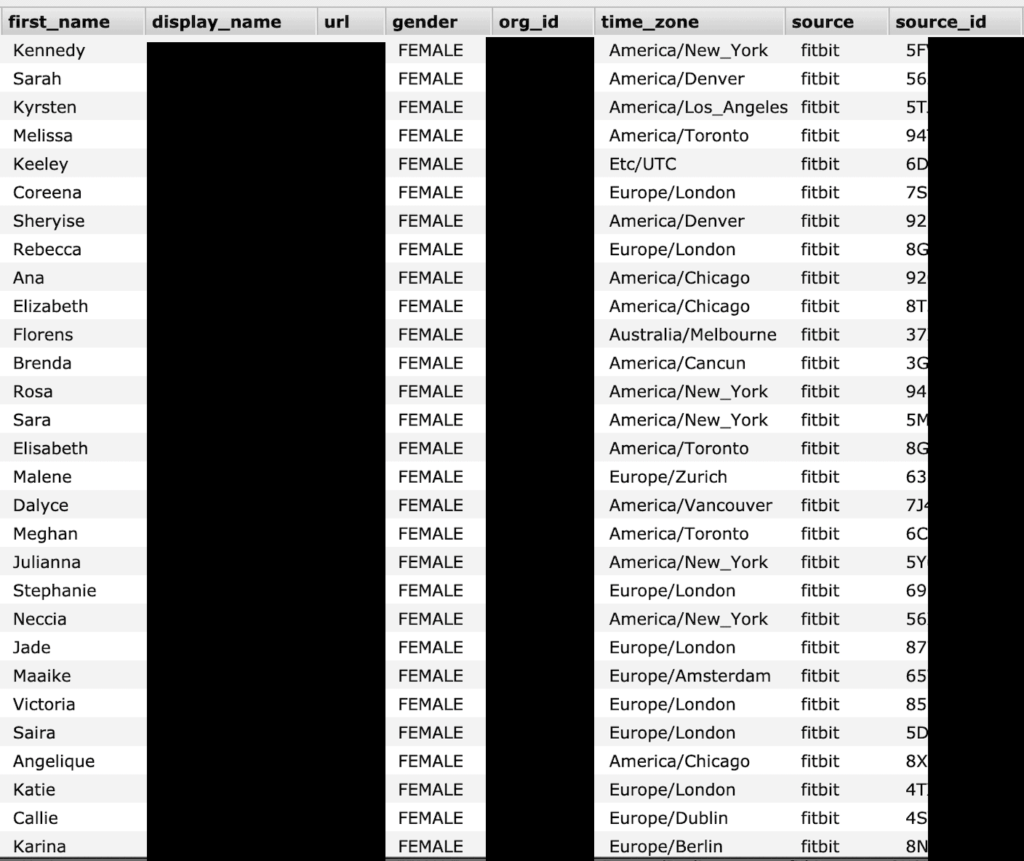

The platforms that can sync data to GetHealth are 23andMe, Daily Mile, FatSecret, Fitbit, GoogleFit, Jawbone UP, Life Fitness, MapMyFitness, MapMyWalk, Microsoft, Misfit, Moves App, PredictBGL, Runkeeper, Sony Lifelog, Strava, VitaDock, Withings, Apple HealthKit, Android Sensor, S Health. As for devices, Fitbit appeared in many listings, and Apple’s Healthkit was on an even more notable number of records.

The types of data that were exposed are the following:

- Full name

- Username

- Date of birth

- Weight

- Height

- Gender

- Location (city/country)

In some records like those coming from the Apple Healthkit, for example, more complex metrics that include blood pressure, sleep patterns, blood glucose levels, and more were also found. In general, there was a lot of phone sensor data as well, depending on the apps and the permissions those had in the source device. As for the location of the users, the data affects people from around the globe.

It is time for people to take their fitness apps and wearable gadgets more seriously regarding the privacy risks they could potentially expose them to. Most modern wearables are now flirting with the health/medical field, and their accompanying apps were evolved to match their upgraded capabilities. As such, in the case of a data leak like the one discovered by J. Fowler, the exposed details are very sensitive. Trustwave says each record of healthcare data is worth $250 on the dark web, indicative of what crooks can do with it.

The period of exposure for the above details is unknown, but the researcher says GetHealth eventually secured the data, so the exposed instance is no longer accessible. As unlikely as it may seem for a database that was indexed in specialized search engines, it may not have been accessed by malicious actors by the time it got secured.