The “ARCHER” Supercomputer in the UK Suffered a Security Breach

- The UK academic research community has taken a blow after “ARCHER” suffered a security incident.

- Hackers managed to access the supercomputer’s platform, so all credentials will now be reset.

- This could be an attack launched from state actors trying to steal COVID-19 research data.

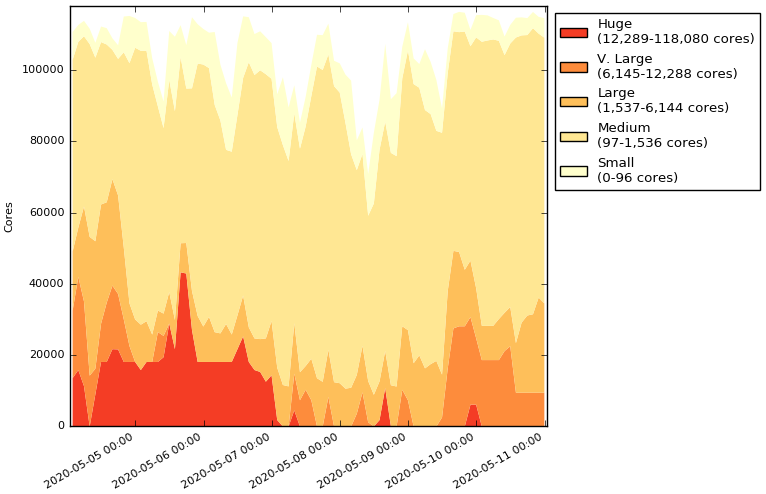

ARCHER, One of Britain’s most powerful supercomputers, suffered a security breach that compromised the login nodes and took the system down for maintenance and investigation. This happened on Monday, causing an unplanned disruption, as shown in the below diagram. Cray joined the investigations since they are the creators of the particular XC30 system.

Source: archer.ac.uk

On Tuesday, the status page of the UK National Supercomputing Service indicated that the unavailability would continue, as the inquiries hadn't been concluded. Any jobs that were running or queued would not be interrupted, but no new jobs could be submitted. Similarly, users could not log in to the system for safety reasons.

Yesterday, the status page was updated once again, declaring that the investigators believe the incident to be a part of a large-scale attack that has affected several academic systems across the UK and Europe. Thus, they have escalated the case to the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) and Cray/HPE and made it clear that ARCHER won’t return to normal service before May 15th, 2020. Finally, a decision to reset all of the existing SSH keys and passwords was taken for reasons of security.

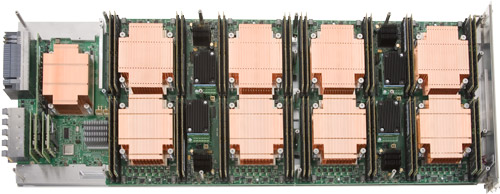

One of ARCHER's 4920 nodes, Source: archer.ac.uk

ARCHER is a 118,080-core beast that costs £43 million ($52.5 million), and it’s used by EPSRC, NERC, EPCC, Cray Inc., and The University of Edinburgh. Recently, it has been deployed for COVID-19 research, and possibly APT actors wanted to access the data, as there have been multiple warnings about this risk since the start of this month. Developing a vaccine for COVID-19 is a race right now, and if you can steal the progress of other countries, it would provide an amazing boost for your national scientific research teams. Machines like ARCHER can simulate the effectiveness of a large number of different molecular structures or potential vaccine ingredients like antigens, stabilizers, adjuvants, antibiotics, and preservatives. Stealing these results is the equivalent of saving time that would otherwise be wasted in running simulations on your supercomputers.

Even if stealing research data wasn’t the motive of this security incident, disrupting the operations could be another possible explanation. This would slow down the research in the UK, allowing other pharmaceutical developers to take the lead. As for how close we are to a working vaccine for COVID-19, this remains a matter of debate. The most optimistic experts in the field estimate that we’ll have something ready within two years, while those who stand at the opposite side of the spectrum don’t believe we’ll ever see a COVID-19 vaccine coming into fruition.