APT41 Malware Intercepts SMS Traffic From High-Profile Targets

- The Chinese hacking group "APT41" is found to be deploying SMS traffic intercepting malware on telecommunication servers.

- The malware can capture communications based on the phone number, IMSI, or even keywords.

- The compromised Linux servers didn’t belong to Huawei, but no further details have been disclosed.

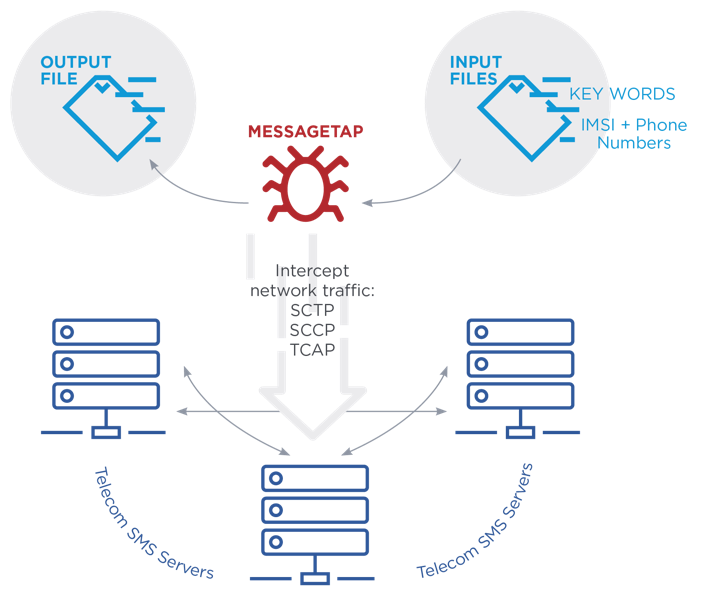

FireEye informs us of a new malware family called "MessageTap", which is deployed by the Chinese hacking group known as "APT41". The malware infects the systems of telecommunications network providers and then uses keywords, IMSI (International Mobile Subscriber Identity) numbers, or phone numbers directly, to steal the contents of the SMS (Short Message Service) communication that corresponds to the set target. Obviously, APT41’s targets are high-profile individuals who hold a particular interest in the context of cyber espionage, so MessageTap isn’t addressed to the broader audience. However, the fact that such an attack exists raises our concerns.

Source: FireEye Blog

FireEye discovered the new malware in a cluster of Linux servers belonging to a telecommunications network provider and operating as a Short Message Service Center (SMSC). SMSCs hold the role of routing SMS traffic to the intended recipient or keep the messages until the recipient connects to the network again. The MessageTap malware is a 64-bit ELF data miner that checks for the existence of two configuration files and attempts to read them every 30 seconds. These two files contain the instructions on whom to target and are deleted from the disk once they are read and loaded into the malware’s memory.

MessageTap is intercepting the SMS traffic and saves it to a CSV file that can be exfiltrated at a later stage. The malware monitors all network traffic that arrives or leaves the servers, using the "libpcap" library to do so. Ethernet and IP layers are included in the interception, so nothing is left out. As we have seen in past stories, other Chinese hacking groups have tried to query CDR (call detail record) databases, targeting high-ranking individuals who were of particular interest to the Chinese intelligence services. However, the case of the MessageTap involves a much more targeted network infiltration and information stealing.

A representative of FireEye told the press that the hardware which was found to be compromised wasn’t coming from Huawei, but he preferred not to clarify whose it was. Possibly, because the researchers aren’t certain about how the infection occurred, and during what stage of server commissioning or operation the planting took place. As for what regular people can do to protect themselves now, the answer is not much really. The responsibility to protect people’s communications lies in the providers themselves, who are supported by reports from firms like FireEye.

Have something to comment on the above? Feel free to share your thoughts with us in the dedicated section beneath, or on our socials, on Facebook and Twitter.