Support for Old GPRS-Era Encryption Standard Creates Security Issues on Modern Smartphones

- Several new models of smartphones still support old network encryption standards from decades ago.

- This creates a set of problems as there’s a way to force them to drop to that secondary choice and decrypt traffic.

- The most shocking finding is that these old algorithms appear to have been deliberately weakened by design.

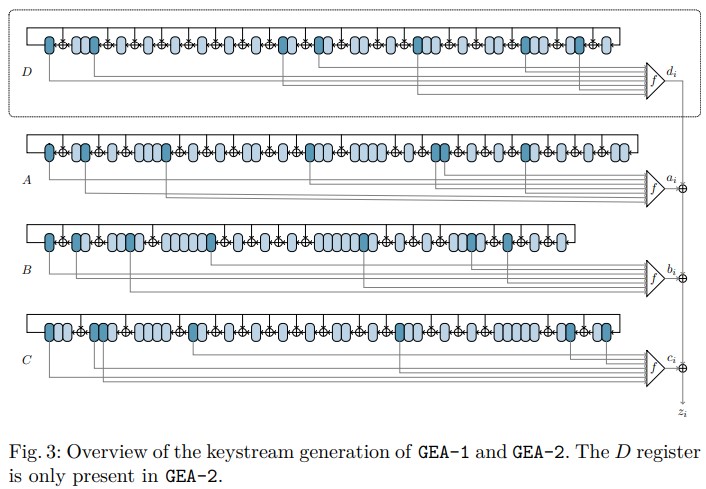

A team of researchers from various European universities has conducted cryptanalysis on old GPRS encryption algorithms to figure out how strong they are. GEA-1 and GEA-2 were used quite a few years ago. However, because they are still supported by some modern smartphone models, they could create data security liabilities if they are found to be weak. As the published paper explains, this is, unfortunately, the case with these old algorithms.

When the GPRS (2G and 3G) service was being rolled out in Europe, the legal situation around encryption was somewhat unclear. As such, the developers of the GEA-1 encryption algorithm had to cripple it and make it less strong. So, while it theoretically provides 64-bit encryption, in reality, it is limited to only 40-bit by design.

As the researchers explain, even 24 bits coming from one frame would be enough to recover the master key. GEA-2 was proven to be stronger, featuring no intentional weaknesses, but it's still breakable if an attacker uses a combination of algebraic techniques and list merging algorithms. For that through, 1,600 bytes of keystream are required.

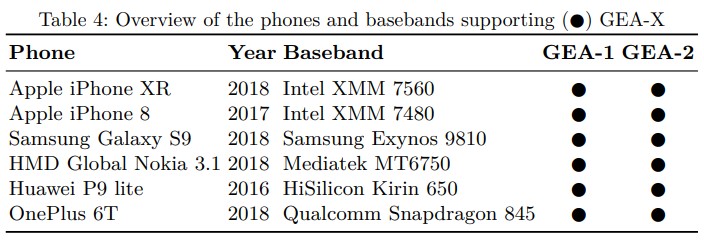

In conclusion, partial security only came with the release of the GEA-3 algorithm standard in 1999, while the latest specification is GEA-5 released in 2018, and which is still unbroken. Due to reasons of compliance with local laws, operator support, negligence, or a mix of those, some modern smartphone devices are still supporting GEA-1 and GEA-2. The researchers characteristically confirmed popular devices such as the Apple iPhone XR, the Samsung Galaxy S9, and the OnePlus 6T.

These devices use these encryption algorithms as secondary backups, but an attacker could force them to downgrade to these specifications and then break the encryption. The two main requirements for a successful attack are for the actor to sniff the encrypted radio traffic of the target’s device, and retrieve the 65 bits of the keystream, preferably its beginning. If this is done, the attacker can compromise the current GPRS session and decrypt all data that comes and goes from the device.

As Professor Matthew Green of the Johns Hopkins Information Security Institute comments on The Register about the paper, law enforcement could easily use some devices called “stingrays” to perform the above attacks, but it is worth noting that the police aren’t the only ones having such tools at their disposal. And the main question that requires explanations for Green is why the GEA-1 cipher was deliberately weakened in the first place, who asked for it, and who got to benefit from it over the years.